My upcoming game Daxolissian System: Espionage includes flight sim levels that take place on an asteroid orbiting the (fictional) star Daxolis, which has an asteroid belt with its own atmosphere making it easy for species from different asteroids to interact. And it means that flight takes place in an atmosphere instead of the vacuum of space. Whether or not it’s possible to have an asteroid belt with an atmosphere is beyond the scope of this post, I’m just going to talk about the flight sim aspects.

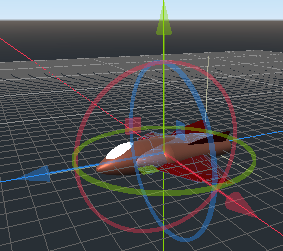

When you’re greeted with the controls you’ll see the terms “roll”, “pitch”, and “yaw”. Those are the three ways that an aircraft can rotate. Roll is rotation around the blue axis in the picture so the wing tips follow the blue circle, controlled on a real aircraft by the ailerons (flaps at the back of the wings). Pitch is rotation around the red axis to make the nose move upward or downward. For the most part, those are the major ways a pilot controls an aircraft -- roll so that

"up" points toward the direction you want to turn, and pitch upward.

There’s also yaw controlled by the upright rudder in the back, which rotates the aircraft around the green axis in the picture and is essentially like steering a car. In practice yaw is just used for small adjustments and not to execute turns on its own, in part because humans tend to be much less likely to puke if you pull off a “coordinated turn” with roll and pitch so people in the plane feel like gravity is pulling downward than if you just yaw so it feels like gravity is pulling sideways, and in the game the effect of yawing is weak to mirror that – it’s useful for small adjustments like lining up shots but not for turning quickly.

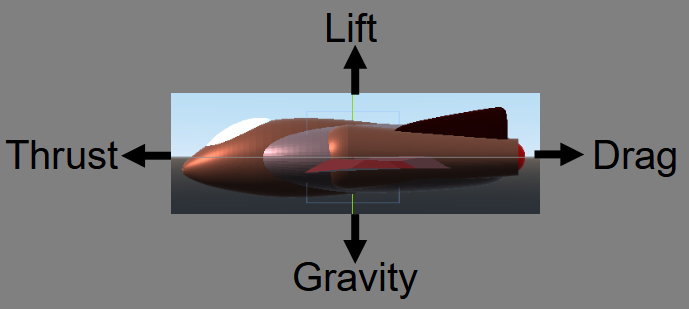

When you’re flying straight and level there are four main forces at play. Thrust from the engine pushes you forward. Drag dampens your motion (in the forward direction or any other direction you might be moving). Gravity pulls you down. And lift from the wings pushes you up. Notably, the amount of lift generated by the wings is dependent on how fast you’re going. In Daxolissian System lift is just proportional to forward velocity. You might notice it if you hit the afterburners to increase your forward speed and see that the increased lift is pulling you upward.

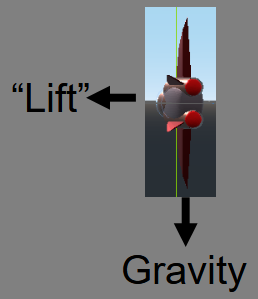

The other thing to notice about lift is that it doesn’t push “up” as in “the opposite direction of gravity”, it pushes “up” as in “toward the upper and more curved part of the wing”. So if you start rolling then the lift produced by the wing pushes less upward and more sideways, and in an extreme case if you’re rolled 90 degrees then your “lift” won’t be lifting the plane at all and will just be pushing sideways. You can still fly like that, but in order to maintain altitude you’ll need to have the nose pointed upward so the thrust is pushing up enough to fight gravity instead of depending on the lift produced by the wings.

That also brings up something that might seem counterintuitive or “wrong” as you’re playing – if you’re rolled steeply then it will seem like the camera is following the plane at a funny angle instead of following right behind it. In fact, that’s exactly how the physics works – the lift from the wings will push you sideways so you really will be moving at a funny angle compared to the camera that’s chasing you.

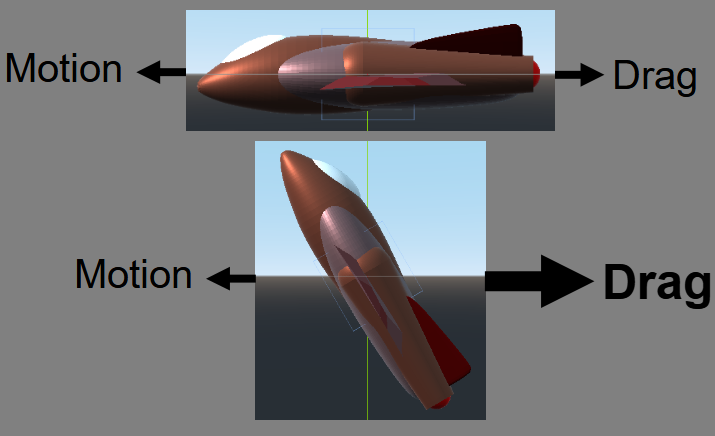

Another thing that might seem “wrong” with the physics is that you might turn very hard but feel like you’re not moving in the direction that you just turned. That’s also how things actually work. The physics in Daxolissian System handles your plane as an object with inertia, and the thrust will eventually get you moving in the direction that the nose is pointing but it will take a bit for the drag from the air to stop the inertia in the direction that you have been moving. I did make drag be related to the angle of attack, so if you’re moving forward straight and level you’ll have less drag than if you’ve just banked hard and you have a broad surface facing your direction of motion. Also, I gave the Daxolissian atmosphere a lot of drag and the plane a lot of thrust so you can change direction fairly quickly compared to an Earthling, which makes aerobatics a lot easier and makes for a funner game. And lastly for those of you who have read this long, a protip is that a good time to hit the afterburners is just after you’ve changed your orientation -- that extra boost will help overcome your inertia and get you moving in the desired direction a lot faster, which can be very useful if a mountain face is approaching.

There are some things I haven’t talked about like stalling. In real life if you try to bring a plane’s nose up to 90 degrees you won’t be flying straight up, you’ll go into a stall where you’re no longer generating lift because your angle of attack is so wide that air can’t flow laminarly across the wing and instead goes into turbulent flow, so the amount of lift you generate (as well as your plane) plummets. I did not model stalling into Daxolissian System: Espionage out of mercy for the players. Similarly I made the plane roll, pitch, and yaw at the same rate regardless of how fast you're moving instead of having them be dependent on the airspeed. And the last thing I’ll touch on is gliding. In real life you can cut the engine and still make some use of the flight surfaces, but I didn’t model it in the game, in part because I made the drag so strong (to facilitate aerobatics) that it wouldn’t have much impact, and in part because I haven’t found great theoretical discussions of directional change while gliding vs directional change due to thrust and which one is really the dominant force in practice. I would've thought that a heavy aircraft (one not specifically designed to be a glider) would have negligible ability to change its direction of motion by gliding without engine thrust, but I concede that Chesley Sullenberger and Jeffrey Skiles successfully executing the Miracle on the Hudson in an emergency situation proves that the gliding effect in heavy aircraft isn't zero.

Hope that’s helpful, and if you’re interested in aerodynamics and flight either in air or space there’s a whole internet of information out there. NASA's aeronautics page would be a good starting point to see what sort of stuff is currently cutting edge while the free eBooks go more in depth.